In Part 1 of this article I explained the importance of extending ones inversions, headstand and shoulder stand. I showed how for meditation to succeed what yogis call prana or amrita (nectar) needs to be accumulated or preserved. In this weeks article I will delve into the technical details and guidelines for extending one’s time spent in inversions. This process needs to be undertaken slowly and gradually over many years, as sudden increases in the time spent in these postures may backfire.

When increasing the time spent in inversions the first step is to slow down your breath as much as possible. T. Krishnamacharya’s idea of headstand was to take only 2 breaths per minute. This needs to be considered an extreme form of practice that needs to be approached slowly. Slow your breath down gradually over months and if necessary over years rather than suddenly. In inversions the blood pressure rises initially, particularly in the head, only to drop off again after a few minutes. If you have high blood pressure you need to take steps to reduce it before working on inversions. Once you have achieved a very slow breath rate in your inversions, start to add breaths, perhaps one every few days. Be sensitive and stop adding on before you experience adverse symptoms. If you do experience symptoms such as headache, irritability, neck pain, ear pain, ringing in your ears, pressure or a fuzzy feeling in your head, you have gone too far and need to decrease your time. Do not be ambitious, and get advice from a qualified teacher.

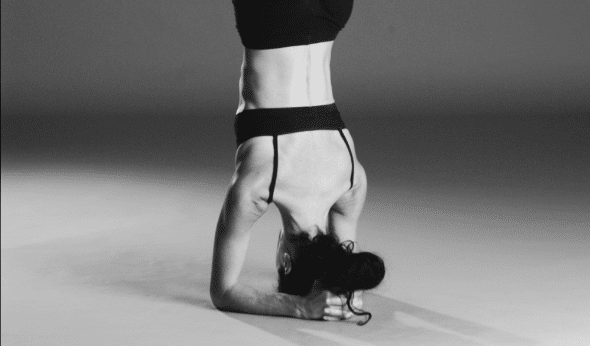

Work simultaneously on increasing the time spent in both shoulder stand and headstand, as both have a beneficial though different effect. Only the strongest and most athletic students should focus all of their efforts on headstands. In the case of both postures, the more vertical and perfectly aligned your body is, the more effective the posture becomes. In all inversions you need to keep the whole body active and all large muscle groups engaged to prevent blood from draining into the head.

In shoulder stand it is essential that you keep the cervical vertebrae off the floor. It is not a neck stand. This means that you need to carry the body on the back of the head, the shoulders and the elbows. Push these three areas gently into the floor to lift the cervical vertebrae off the floor. If they are still touching the floor you have to use a blanket placed under your shoulders (not under the head). This will create additional space to prevent the jamming of the cervical vertebrae.

The other important point about the shoulder stand is that it should be performed with a short neck, that is by pulling in the head like a turtle. While in all other postures we try to keep the neck as long as possible (by drawing the shoulder blades down the back, engaging both the latissimus dorsi and the lower trapezius), it is the shoulder stand in which the opposite action is performed. In this regard the shoulder stand is similar to Jalandhara Bandha, the chin lock. This bandha is exercised particularly during internal breath retention (antara kumbhaka). Prior to placing the chin down on the chest, the chest is lifted upwards. This movement causes exactly the same shortening of the neck as if you pressed the shoulders into the floor during the shoulder stand. During shoulder stand the chin needs to firmly press against the sternum (breast bone).

When extending your headstand the most important point to keep in mind is carrying most of your weight on your arms and shoulders and not on your brain. If you allow yourself to ‘dump’ all weight on your head and use your arms for balancing only, the intracranial pressure will rise too high. That’s why it is important to be conservative with extending your time spent in the headstand. For most students it makes sense to stay slightly longer in shoulder stand, which is less taxing. Gradually, however, we should attempt to increase the length of the headstand to be even to the time spent in shoulder stand.

The question of how fast you can extend time spent in inversions is determined by your age and general condition. If you are young, athletic and in pristine health, you may add on breaths quite quickly, whereas an older person, or one with a chronic health problem might have to do it very, very slowly. Some teachers are of the opinion that people over 50 should not embark on taking on extended inversions. I have explained the shoulder stand and headstand in more detail, with photographic images, in Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy. P. 51

If you breathed only twice per minute both during shoulder stand and headstand and take 25 breaths in each you would spend around 25 minutes in both combined. This would be a good goal to work towards initially. Of course you need to take into consideration how much time you can devote to yoga in total. My general impression is that modern students spend too much time in acquiring an athletic, fancy, flexible asana practice. My suggestion is to limit such pursuits to a maximum of about 90 minutes per day and rather divert more time to kriyas, pranayama, inversions and meditation as described in this book. You would then arrive at a more holistic program for yoga methods rather than placing all your eggs in the fancy asana basket.

Please note that, however much energy you put into your inversions, they cannot by themselves bring about yogic states. In this regard they are similar to most other yogic techniques such as vegetarianism and general asana practice. It is only in combination with other methods such as pranayama, kriya and yogic meditation, as a combination, that they achieve great power. If you slowly and steadily, and in an organic fashion, increase the duration of your inversions over the long term, you will find that they do empower your meditation and pranayama, but they will teach you also to pass on the many so-called ‘opportunities’ in life that we would better not get involved in. This is an effect of amrta (lunar prana) being arrested in the higher chakras, which in itself is Gorakhnath’s physical approach to pratyahara, the fifth limb of yoga.

This is an excerpt from my 2013 text Yoga Meditation.