As the four Vedas were originally one, so all yoga in the beginning constituted one single system, sometimes called Maha Yoga, the great yoga. The separation into Bhakti, Karma, Hatha, Raja Yoga etc. is artificial, as they are only aspects of the one yoga. The various aspects of Hatha Yoga constitute nothing but the physical aspects of meditation. They are the groundwork and supports on which the structure of meditation is erected. It then describes the mental discipline of yoga, called meditation or Raja Yoga. After that are discussed the results or fruits of physical and mental yoga – the spiritual aspect or Bhakti Yoga. This process finally merges into the conclusion of yoga, the Jnana Yoga, which should only be attempted after all of one’s duties in life and towards society have been fulfilled.

In the Bhagavad Gita Lord Krishna said that the original yoga was lost due to the lapse of time.[1] It is for this reason that today we find the original yoga splintered into many petty techniques and schools that by themselves cover little terrain. If individual yogic techniques are practised out of context, there is a low probability of success. Patanjali says that all eight yogic limbs need to be practised for yoga to succeed.[2] It follows that practising asana is not enough. There is absolutely no evidence within the body of yogic scripture that asana alone will get you to your goal. On the other hand, with each limb or ancillary of yoga that you add to your yogic tool box you potentialize the power of the practice and the probability of its success.

Many yogis today are stuck at asana because they think they need to reach an unrealistic level of performance before integrating higher limbs. But life is too short to entertain that thought: in order to have a realistic chance at succeeding with yoga you need to integrate the higher limbs as early as possible. The earlier you start some form of basic pranayama and meditation, the earlier you will experience inner freedom. If you dedicate even 10 minutes per day to each, this will enhance all other aspects of your life and practice. Do not wait until you have achieved some mythic level of achievement in asana that probably will never come. Some people have invested 30 years of daily practice in asana but in the end have found themselves with nothing but a trim body. Believe it or not, this trim body will, despite all of your asana practice, fail you and go six feet down (or up the chimney depending on your preference). Do not invest all of this time in nothing but asana: in order to derive any lasting fruit from asana you need to combine it with pranayama and meditation.

Patanjali calls the architecture or structure of yoga ‘Ashtanga Yoga’. This Ashtanga Yoga engulfs and involves all other aspects and schools of yoga. While my previous books have explained Patanjali’s yogic limbs of yama and niyama (ethical precepts), asana (posture) and breath work (pranayama), this volume deals with Patanjali’s limbs five and six. He calls these limbs pratyahara (independence from external stimuli) and dharana (concentration), and this text describes their essential and important techniques.

While success in dharana and pratyahara can be measured in a quantitative way, limbs seven and eight – dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (absorption) – are qualitative limbs that are the result of pratyahara and dharana being practised precisely and to a deepening extent.

Meditation is only yogic meditation if it is built on certain yogic principles. During more than 30 years of research and practice I have identified 18 laws of meditation, which are described in this book. With this number I have, of course, also paid respect to the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita, which contain 18 chapters. This is the tradition in which I grew up spiritually. In saying this I do not mean that this tradition has a monopoly on truth. The opposite is the case. I am offering modifications to this method that may enable practitioners of other traditions to practise it without experiencing any conflicts.

There is one underlying truth in all religions and spiritual philosophies, and that is the experience of divine love (whether it be called by these words or not). If that love is experienced we can make a contribution to human evolution and society. We can contribute to a life in unity despite diversity and in harmony with divine law. Spiritual illumination and divine revelation are not something remote that only a few chosen can attain. On the contrary it is our birthright and divine duty. The meditation technique described herein has the power to deliver it. On the face of it this may sound like a bold claim, but if you practise the techniques associated with the 18 laws you will find out for yourself.”

© Gregor Maehle 2012

[1] Bhagavad Gita IV.2

[2] Yoga Sutra II.28

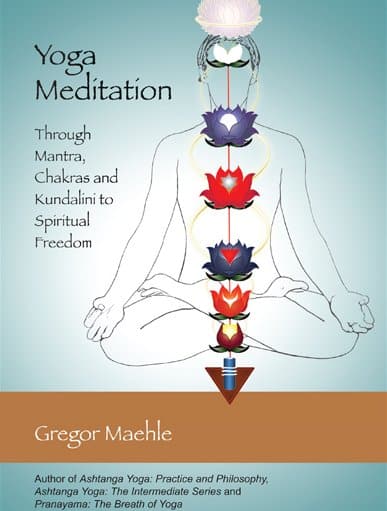

An excerpt from my fourth book, Yoga Meditation: Through Mantra, Chakras and Kundalini to Spiritual Freedom.