One of my biggest frustrations with being associated with Ashtanga Yoga is that other yogis perceive that my asana practice and thereby the asana I teach must adhere to what is known as the ‘traditional’ form (I place tradition here in inverted comas to refer to the popular Jois tradition and not the traditional Patanjali Ashtanga Yoga, which is actually what I do practice and teach!). And many have a negative impression of this ‘tradition’. This negativity stems from Ashtanga’s reputation of being dogmatic, inflexible and hard core. Actually, that’s not a criticism of the practice itself but of the attitude of many Ashtanga Yoga teachers. I practice and teach in a way that adapts the asana practice to the individual’s needs using safe, sound biomechanics and a compassionate approach.

Gregor neatly categorises students into four groups and of course individual students may need to transition between these groups depending on their energy level, injury, age, etc.

Category one has the ideal body for Ashtanga Yoga and can always learn and practice the postures as in the orthodox sequence. Category two has to sometimes switch to therapeutic sequences or alter the series to some extent. Category three has such limitations (for example extremely tight hip joints that prevent half-lotus postures) that the sequences have to be permanently altered but can still be recognised as Ashtanga-inspired. The fourth category of students has such physical limitations that they need to practice a purpose-built therapeutic sequence that may not even be close to Ashtanga Yoga.

Important here is the ability and freedom to modify the asana practice to suit the individual rather than forcing an individual to fit the form. This applies to individual asana, sequences and entire practices. I would treat each of these categories of practitioner differently, catering to that individual’s ability with an aim to holistically nurture that person whilst they explore their possibilities and develop their potential, safely. In my Self Practice classes anyone who has a self-practice is welcome, from advanced series practitioners to those who are doing a practice that is very limited in movement. Everyone deserves to practice, whatever their capability.

However, if you reward students with the next asana, the next series and a teaching and certification system based on physical advancement in asana you can predict that they will become asana-ambitious. The inherent message in this system is that they’re not good enough until they are ‘advanced’. Advanced asana is not a reflection of the perfection, beauty, and divinity that is our true nature. And in the Ashtanga Yoga system there is also no method taught that teaches students how to realise that (more on that in future parts). This system has consequently led to the myth that one is/becomes a great yogi by performing advanced asana. And that belief has led to sometimes irreparable injury and suffering on more than only physical levels. This also constitutes spiritual abuse.

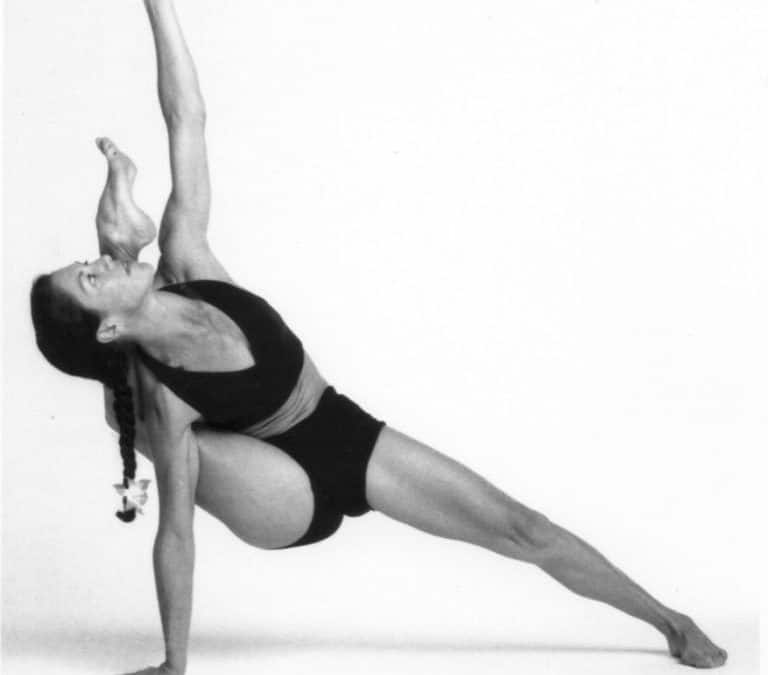

The un-yogic hierarchy of asana achievement in the Ashtanga system is what drives students to incessantly strive to go deeper and deeper into postures, which does not necessarily equate to greater benefit. It is, however, greater wear and thereby potential repair of joints, which is one of the known factors in the development of osteoarthritis. In regards to flexibility too much of a good thing often transmutes into a bad thing. For example, back bends are very therapeutic, however, the extreme of reaching back to hold your ankles requires lengthening the long ligament on the front of your spine to such a degree that you may destabilise your spine. It is not uncommon for yogis to displace the vertebrae at the peak of the curve in their low back (L3) from practicing extreme backbends or being over-zealously adjusted in the same. Previously, without questioning, I have been there and done that myself. Now I see that this is what makes yoga look like a circus.

Also, there are aspects of the practice that are not congruent with its current audience. For example, Ashtanga Vinyasa would have been designed for a population who had open hips. This means that other postures where the knees are less vulnerable may be better to commence hip opening than the half lotus postures. And Badhakonasana might be an important posture to include although it comes after many more advanced postures. In this way the teacher needs to intelligently apply asana that makes the practice accessible to the student rather than going through the motions to uphold a ‘tradition’ that is not applicable and does not serve the person in front of them. Yes, this does require that the teacher has a good level of experience and is why those some practitioners who could achieve postures with little effort often cannot teach them to those less capable.

Traditional teachers will argue that they wish to stay ‘true to the form’, however, this has often involved (presumably unintentionally) breaking the student to fit that tight, narrow box. I have experienced this personally as a student; seen students struggle and abuse themselves as a teacher; and witnessed the destruction of this imposition on numerous occasions as a therapist. The traditional adjustments given by Pattabhi Jois (and unfortunately adopted by many of his students seemingly by osmosis and certainly not by informed consideration) were often forceful and too often injurious. The last thing any teacher wishes is to harm another. It certainly is not necessary. As a teacher one must look to the needs of the student and not to upholding a purity that exists in our ideology, especially when that ideology is to the detriment of the individual before us.

It concerns me that as teachers we may be unawares encouraging a culture of physical and/or spiritual abuse by teaching students to continually strive for more: more flexibility, more strength, more postures, more sequences. We become a consumer of asana, flexibility and greater physical prowess just as we are consuming everything else on our Earth! I often ask students: ‘What are you practising?’ Ambition? Striving? Discontentment? Or exploration? Awareness? Appreciation? Contentment? Teaching is an act of service and needs to serve the student. As a teacher I attempt to read my students’ needs and to meet them where they’re at. That doesn’t mean not exploring their potential but to explore without an imposed set agenda. And I consciously dispel the ridiculous belief that they are any less a yogi for which asana they can or cannot do. We each need to treat ourselves like we treat those we love most and with full respect for this miraculous, sacred site that we inhabit.

Yoga is an introspective practice, which gives us the opportunity to practice interoception, i.e. being receptive to our internal environment, being able to listen and respond to our body and our innermost voice. This protects us physically and guides us spiritually. True asana means being embodied versus using our mind to conquer our body. That’s torture. That is abuse. Give yourself permission to practice honestly, a practice that nourishes your whole being, without self-coercion or the pressure to fit any outcome or even an out-dated version of yourself. Practice with love for yourself and your body. This is an opportunity for the tradition to be enhanced by new understanding. The essence of yoga is not in any order of postures but in an attitude of respect and love, service and humility and freedom that brings liberation from our conditioning, not one that adds to it!

Monica

For those of you who prefer to read in French here is a French translation of the article.

https://yogashalarennes.fr/2018/12/10/lashtanga-nest-pas-le-probleme-son-enseignement-lest/

All this misunderstanding comes up in practitioners, because of the lack of fundamental knowledge of the entire science of yoga.

“Yoga refers to a process in which people tries to get to know their original self through taming and controlling the body and the mind (svarupa) and achieve the ultimate source of existence [the Universal Self (Brahman), the Super soul dwelling in the heart (Paramatma ), or the Supreme Person, God (Isvara, Bhagavan)]. The connection with this ultimate source is the highest purpose of yoga. ”

Of course, this process takes place at different levels. There are certain elements on the physical (gross physical) level, there are some on mental (subtle) and those that effect on the transcendental (spiritual, not material) level. Of course, these three dimensions of the existence are interacting constantly. Thus, the yoga of the physical body helps to preserve the cleansing of delicate physical plane and peace of mind beyond health, meanwhile bringing us closer to understanding the spiritual dimensions as well. It can be seen that the theoretical aspects of yoga beyond its practical aspects are important to the process of fulfilling its function.

II. Practical approach to the yoga-process

Creating and considering the complete definition of yoga we can see that yoga can be established only if the people, searching for the purpose of life through the truth and self-realization, proceeding with the support of a tool, proposed by the authoritative yoga literature, through regular practice, and determined to reach non-financial aims.

Traditionally these tools include several species. Renunciation has a great role (physical, material, mental, emotional, etc.) that helps to squeeze into the background the material-physical self-identification, and gives way of understanding ourselves as spiritual beings. The transcendental knowledge nurtures this spiritual self-identity, teaching the yogi about selfness and God. The knowledge carried out by selfless deeds, meditation, devotion to God, and the combination of mentioned in an authentic, traditional way are both important in the yoga tradition.

Tools and trends used in the yoga

According to the tools, the yogi is using to achieve the self-realization; different trends are distinguished in yoga. There are three (or four) known major trends: karma-yoga, Jnana-Yoga, Ashtanga yoga and bhakti yoga.

The trends are characterized not only by the tools it is using, but by their aims as well. This may be the reach of the absolute, God, impersonal Brahman energy, or partially personal characteristics of Paramátma, or personal Bhagaván, Ísvara; or those seeking only to preserve the health of the physical body, or the mystical abilities available (Siddhis) may also constitute the target for some people. So karma-yoga is the liberation, Jnana-Yoga is the cessation from suffering and material liberation (brahma-szájudzsja-mukti), Ashtanga Yoga is liberation (in the form of brahma-szájudzsja-mukti or isvara-szájudzsja-mukti), and bhakti-yoga aims devotional service to God, in which the release occurs automatically in the form of számípja-mukti. In this case the yogi or practitioner wins God’s personal spiritual companionship after the release of material existence. The brahma-szájudzsja means the merge into the Brahman, the Isvára-szájudzsja into the Paramátma, and the perfect union with Him. It is understandable that the quality of the aims is defining in the individual tendencies.

In terms of the adopted instruments the karma-yoga is using the karma or the acts on the process of self-realization, in the form of so-called altruistic deeds, paying a big role by renunciation in it. In the Jnana-Yoga, the yoga of transcendental knowledge the priority is the process of spiritual knowledge and meditation. Patanydzsali’s eight way of Ashtanga yoga system can be classified in this trend as well. The bhakti-yoga, or the awakening of dormant love of God and the service of God is the device, in which the most important practice is the repetition of His holy names (mantra meditation), listening to Him and remembrance of Him.

Whichever process is considered, we will see that all the devices can be found in each process, but at different rates, with different emphasis and of course in order to achieve other goals.

Can I build muscle doing ashtanga with fibromyalgia. I have done every exercise program out there..

Do you have videos for teaching at home? Tricks to do certain positions. Breakdowns of each movement’s like David Garrigues?

Hi Barb

Sorry I don’t have the videos you describe, just a few on YouTube which are therapy based.

Namaste, Monica

Dear Dr. Gauci,

thank you for this excellent article! It would be good if more Ashtanga Yoga teachers had your practical approach to teaching. Unfortunately, the conventional ‘wisdom’ (supported by many renowned yogis) has it that keeping to Jois ‘tradition’ is the best one can ever get. I am not the teacher, just a student (now primarily learning from the books of your Husband). This year I have started Ashtanga Yoga with a quite demanding teacher (at least for me). My first contact with yoga (not Ashtanga) was years ago, but I did not practice on a regular basis. Now Ashtanga Yoga is my path to liberation. Unfortunately I cannot practice anymore with my teacher. The pace of learning subsequent asanas was too fast for me. As soon as I could do any particular asana, 5 minutes later I was expected to learn the next one (of course more advanced, even from the Second Series, while my internal voice was telling me I still needed to practice some basic asanas from the Primary Series) . Basically, I had no time to feel how and to what extent the previous asana worked with and in my body and mind. Now I feel comfortable with my practice at home, but of course I would love to have a teacher like you around me. Thank you once again! All the best for You and Your Husband.

Thank you Katarzyna.

Namaste, Monica

Wonderful, wise article Resonates deeply with me, having extremely tight hamstrings, tight hips and moderate Scheuermann’s disease of the spine. I would be interested to know if you would go so far as to allow a student with my challenges (who can get through Primary with many modifications) to practice the first third of Intermediate to access the various twists and back bends (excluding Kapo), and if so, after which Primary pose.

Thank you Dane.

I recommend all my students to add in the first intermediate backbends if they are practising primary regularly. For me these are necessary preparation for Urdhva Dhanurasana which is an advanced posture that Pattabhi Jois decided to move to the end of each sequence, including primary.

It’s always important for teachers to evaluate each student to see how they can best balance their body and would give other postures based and this.

Namaste, Monica

Dr Gauci, this is by far the most mind blowing article on the integrity of Ashtanga Yoga and also the most challenged. I must say that I teach very closely as you suggested. Through compassion and respect rather that an adamant to “tradition”. Thank you so much! You have sealed my fate. I love this.

Thank you for your positive affirmation Azmi. It is great to hear that other teachers are doing the same. Namaste, Monica

Hello! This article was very well written, and I really appreciate your perspective and voice in this dialogue about the Jois Ashtanga tradition. I have learned more about the Jois tradition and Jois himself, and I really do not want anything to do with it. I would like more information on the original Yoga that Jois co-opted. I never liked the hierarchical nature of Jois Ashtanga. I never liked that it was primarily male. I didn’t like that it felt like he tried to “own” the lineage of Yoga. Then I learned about Jois sexually assaulted women practitioners, and I have had enough of Jois Ashtanga. I will never do it again.

Thank you Jay!

Namaste