Yoga Sutra I.14: One becomes firmly established in practice only after attending to it for a long time, without interruption and with an attitude of devotion.

We might practise for a while and then all at once find our past conditioning overwhelms our practice efforts. We may suddenly develop anger, greed, pride, lust and envy, and wonder how that can be after all this yoga. How can we avoid succumbing to such impulses?

Patanjali suggests it is by being firmly established in practice. This cannot happen all of a sudden: we are bound to have a yoyo practice at first. We may make good progress one moment and the next moment find ourselves back in our old conditioning. To really become established one needs to practise for a long time, without interruption and in a devoted way.

What does a long time mean? A year is not a long time. A decade is more to the point. Several decades would be realistic. The ancient rishis are usually depicted with long beards, and they are said to have reached freedom from bondage after a lifetime of study and practice. True, some teachers have reached incredible wisdom at a young age: Shankaracharya composed the Brahma Sutra Bhasya when he was twelve. That this is not the normal course of events is reflected in the fact that both teachers are considered in their respective cultures to be of divine origin.

The average yogi cannot expect to be established in truth through a few years of practice. A ‘long time’ means we make a commitment to practise, however long it takes, and are not perturbed by any setbacks. The Bhagavad Gita explains that all actions are performed by the Divine only, and so the fruits or results of those actions belong only to the Supreme Being. If I can admit that the one practising is not I, then I will not expect results.

According to Patanjali, it is prakrti (nature) that practises, and we are only looking on. The Bhagavad Gita has it that the Divine operates prakrti (creative force/ nature), and so performs all actions. In both approaches, if we give up the idea of ever getting anywhere with our yoga, then we have arrived at the destination, the present moment, now. However long the practice may take does not matter any more, since we have arrived already.

To practise without interruption means to do one’s formal practice daily. Some really clever people have said, ‘Yes, but if you are tired, exhausted and don’t have the time or energy to do your practice, doing it will have a detrimental effect anyway.’ This is a reasonable thought, but we should ask ourselves why we are exhausted and have no energy and time. Possibly we spend too much time running after money, or our social life takes up too much energy. Alternatively, we might have eaten too late or too much the day before or have not rested enough. Swami Hariharananda Aranya says that uninterrupted practice means constant practice. He is not referring to one’s formal practice but to mindfulness and watchfulness.

The last of Patanjali’s three parameters for establishment in practice is to practise with an attitude of devotion. An example of practising with a bad attitude is to practise because one thinks one has to, for whatever reason, but actually hates what one does. This could be because:

We think we have to get our frame into shape, so that others desire us.

We think that, when we exercise postures more proficiently than others, we are superior to them. (The same can be said about practising meditation and samadhi.)

We practise because we want to get any type of advantage over others, be it physically, mentally or spiritually.

To practise with devotion is to remain grateful for being able to practise at all. It is great good fortune to have come across yoga in our lifetime. Many people have never heard about it or are never properly introduced to it; others live in a war-torn country or in economic crisis, both of which make yoga practice difficult. Again, if our body is crippled or our mind is deranged, yoga will be more difficult. It is good to keep these points in perspective. If none of them applies to us, we are in a fortunate position and need only to sustain a practice and an enthusiastic attitude towards it.

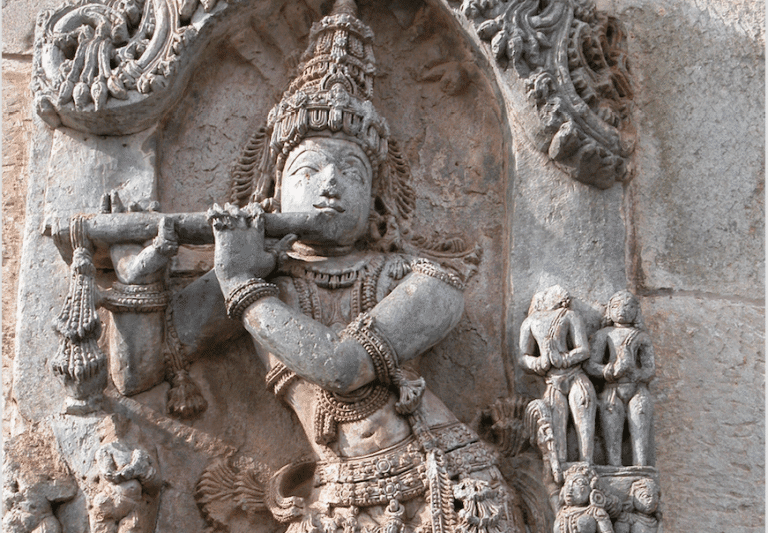

Practising with devotion also means that our practice is performed with an attitude of prayer. Asana practice truly should be prayer-in-motion. Once we become aware of the fact that our life is nothing but a cosmic intelligence enacting itself through. With this awareness then we can surrender to the breath and find that the breath moves us and that we enact neither breath nor movement. We will find then the truth of the above quote in the Bhagavad Gita, “All actions are performed by My Creative Force. Only a fool believes to be the doer.” At this point our practice will become effortless.

This is a modified excerpt from my 2006 text Ashtanga Yoga Practice and Philosophy.

Hi Gregor,

What is your opinion on current standard exercising techniques like cardio (running, biking, swimming, etc…) and weightlifting or strength-training? Where does that fit in to practice?

Do we not need those if we do an ashtanga vinyasa practice? A claim I’ve often heard is that it’s important to build strength through strength-training like pushups, dips, etc… so that we don’t hurt our joints during asana practice.

I’ve also heard things on the internet that if you run or do cardio too much, then you lose prana, and only asana is safer in that respect. I can’t tell whether they have a point or not.

Thanks!

Hello Mark,

Traditional Indian yogis such as T. Krishnamacharya sneered at Western yogic exercises as they were conducive only to muscles and not to prana and nadis, i.e. they considered them unspiritual. K.P. Jois even once wrote a letter to the Yoga Journal that included the sentence, “It would be a shame to lose the precious jewel of liberation in the ignorant mud of body building.” I’m much more open to other forms of exercise than the view described above, but a few pointers nevertheless:

1. To my knowledge the injury rate in sports, endurance and strength training is much higher than in yoga (given that’s its done with a reasonable attitude). So the argument that sports reduce yoga injuries doesn’t stack up. I think on the other hand yoga should be done to reduce sports injuries. : )))

2. If somebody wants to supplement their yoga with other forms of exercise then that’s a private choice and we live in a free country. But it should not be part of teaching yoga as particularly Ashtanga Yoga contains a huge strength aspect.

3. The original idea of yoga was that a physical practice (asana) was used to supplement pranayama and meditation, i.e. the spiritual aspects of your practice. It worries me if now a second physical practice is introduced to supplement the first physical practice. This is also what worries me about Yin Yoga. Part of the Yin lure was that it was to balance the too vigorous Ashtanga (i.e. again also here a second physical practice is introduced to fix the first one). Now some people seem to think Ashtanga is too demure and other, harder workouts need to be introduced.

4. The most important thing to introduce is a pranayama practice, i.e. sitting Nadi Shodhana, Kapalabhati, eventually Bhastrika and kumbhakas. Also, a yogic chakra-Kundalini meditation practice needs to be introduced, for Ashtanga vinayasa to succeed.

5. If strength and endurance training is introduced because of personal preference one needs to make sure that this does not come off one’s efforts invested into Ashtanga Vinyasa, i.e. one’s 6-day per week kick-butt practice needs to be maintained and any extras need to go on top of that. And hopefully without reducing one’s efforts in pranayama and meditation. And here we have the head of the pimple. How much time exactly do you have to spare?

Hope this helps

Warm regards

Gregor

Thanks for the message. Yes, good points that yoga has much less injuries than sports, and I agree that adding Yin on top of Ashtanga is beginning to make life pretty complicated, and who has time for all of this.

I completely accept the necessity of the Ashtanga practice as preparation for pranayama and meditation. I’ve noticed that good meditation posture makes my meditation zoom forward compared to without it. But then the more direct question becomes what is the specific reason for ashtanga?

To put it more matter-of-factly, is the goal of ashtanga vinyasa to get to the strength and flexibility to do long breath retentions, hold padmasana and be able to do inversions for 5 min with sthira + sukham? Is that how we should evaluate our practice?

No matter how much bhakti I try to put in, it’s so easy to get ambitious (happens every session 🙂 and focus on getting to intermediate/advanced series, but then I have to remind myself, that probably isn’t what Krishnamacharya cared about.

Hi Mark,

I have written in several of my books of the multitudinous benefits of asana practice. I will collate some of them and elaborate on them to create an article. It will involve sutra I.31, i.e. that yogic obstacle also surface in the body. Then we do on to the panchakosha doctrine of the Taittiriya Upanishad, which explains that the body is the decelerated strata of the mind and nothing but crystallized thought and karma. That all needs to be explained to really understand asana.

I’m just working on rectifying back-to-back climate-change induced flooding events which damaged and partially washed away our driveway. But hopefully that won’t take too long and I can work on that article.

I’m also working on a book on Bhakti (which is a lengthy process) but the problems you describe you would find addressed in How To Find Your Life’s Divine Purpose.

Talk soon

Gregor