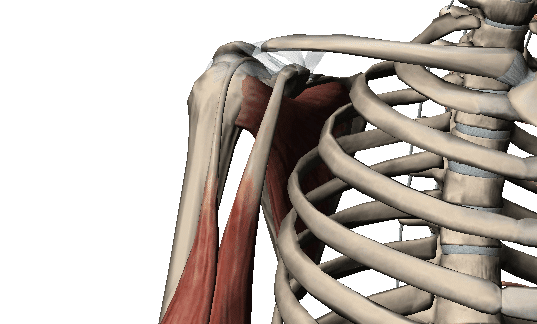

The most common shoulder problem I encounter in yogis is one that is often overlooked even by professional musculoskeletal therapists. It is the displacement of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle from its bicipital groove. This usually causes pain at the front (anterior) of the shoulder, which sometimes radiates down the front of the arm even to the hand. Other symptoms include not being able to freely push up and open the shoulders in Urdhva Dhanurasana, discomfort when putting the hands into prayer on your back in Parshvottanasana or when binding the feet in lotus postures and a general sense of weakness in all phases of the vinyasa, especially the inability to attempt a pike.

This injury can result from poor posture, which usually translates into poor form, especially when the stress of bearing weight on the hands is added. In experienced yogis this injury often results from an excess of jumping up into handstands or pikes during vinyasa transitions (jumping up or jumping back). This becomes problematic when the internal rotator muscles of the shoulder dominate the movement. The long head of the biceps, besides performing elbow and shoulder flexion and supination of the forearm, also performs external rotation of the arm. When weight-bearing on the hands the forearm is pronated, and if the internal shoulder rotators dominate, the bicep becomes inhibited. As a shoulder flexor biceps brachii is relatively weak and the repeated action of jumping up into handstand or a pike then puts it under considerable strain making it susceptible to displacement.

The internal rotator muscles involved are pectoralis minor, subscapularis, the anterior portion of the deltoid and pec major. I hate to pick on pec minor, however, it does seem to have a ‘short muscle syndrome’ and is the most prone to being overactive. Its contribution to the ubiquitous forward head posture and rounded shoulders makes it commonly shortened. Besides its role in posture it performs an array of other functions: shoulder blade protraction, internal rotation and downward rotation, as well as having a vital role in breathing and gait. This means that when pec minor is overactive it can have synergistic dominance over a variety of other muscles, namely those that perform the opposite actions.

What To Do?

Well let’s start with remedying the problem and then we’ll look at how to maintain a happy biceps tendon as well as preventing the problem from reoccurring. This process has a few steps. Firstly it involves turning down the overactive internal rotator muscles, replacing the biceps tendon in its groove and then strengthening those muscles that have become inhibited. Even if you do not have access to a professional musculoskeletal therapist you can do all of this to yourself.

Pec minor is the most common culprit that needs down-regulating but any or all of the other internal rotators can be involved. Check them all for trigger points or muscle spasm and release them by holding pressure on the sensitive spots until the discomfort dissipates. You can also release pec minor by using a ball between you and the wall. This needs to be done at least twice per day. If your surface anatomy is not up to scratch check out this video link where I’ll show you where and how.

The tendon of the long head of the biceps normally lies in its groove between the lesser and greater bony tubercles. For this reason the bicipital groove is also known as the inter-tubercular groove. When displaced the tendon moves medially to lie over, or in severe cases, on the inside of the lesser tubercle – hence the discomfort! To replace the biceps tendon we need to simultaneously slip the tendon over the lesser tubercle towards its groove. This is done whilst internally rotating the arm, which brings the groove closer to the tendon. Follow this link to see how it is done.

Correction, Maintenance & Prevention

The final but vital step toward correcting, maintaining and preventing a recurrence of this problem is to reactivate those muscles that have been inhibited by the over-dominant muscle(s). It can be challenging to assess yourself as to which muscles are switched off. Common are the middle trapezius, external shoulder rotators, lower trapezius, serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi. If you know which muscles are not engaging you can isolate and activate them with specific exercises. If you cannot feel which individual muscles are involved, good sound use of the entire girdle of shoulder muscles when weight bearing on your hands will usually call these muscles into play. Be attentive to which actions you find most challenging and work on regaining a balance of strength over your entire upper body and shoulders.

Start by place your hands so that when weight-bearing the pointing finger points straight ahead, instead of the middle finger, to alleviate any frictional stress on the biceps tendon. Be sure to keep the lower trapezius muscle activated by not allowing the upper trapezius to dominate and elevate the shoulder blades. To gain and maintain a good balance of shoulder muscle activation work from the hands up. Ground the base of the thumb and pointing finger whilst lifting the web or ‘instep’ of the hand. This lift is imperative to avoid over activation of pec minor as well as to distribute weight to the outside of the hand. This will inspire the external rotators to engage. Connect this lift of the instep all the way up to the inside of the shoulders and to a strong enough degree that you feel the inside of the shoulders broaden (this is especially important when lowering into Chaturanga Dandasana where the biceps is under eccentric load). Now push out through the outside edge of the hand. You should feel the back of the chest and shoulders broaden as the serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi come into play. Via connective tissue (the thoracolumbar fascia) the lats connect our arms back into our core. This connection is vital to achieve the stability that is necessary to build adequate shoulder strength. (For more on the connection of how the actions of the hand relate to the shoulder muscles see my blog ‘Mapping the Hand’).

Once you have alleviated your shoulder pain you can begin to build more shoulder strength. Hanging from your arms is an ideal exercise to activate the important lower trapezius and latissimus dorsi shoulder stabilising muscles.

One of the best ways to maintain length in the pectoralis muscles and fascia is in the bound hand position in Prasarita Padottanasana C. In this posture tuck your pelvis under and feel the enhanced stretch on in the chest area. You can also adopt this arm position in Shalabasana or warming up for Urdhva Dhanurasana. Try this exercise to  stretch pec minor, turn down all the internal rotators and activate the external rotators, retractors and depressor of the shoulder. I call it the Fledgling.

stretch pec minor, turn down all the internal rotators and activate the external rotators, retractors and depressor of the shoulder. I call it the Fledgling.

Lie on your back with your arms at shoulder height. Bend you elbows to 90 degrees. Draw your shoulder blades toward each other to engage the middle trapezius and depress them to engage your lower traps and lats. As you lift the elbows off the floor and up toward the ceiling, press the back of your hands or fists into the floor. This action engages and strengthens the external rotator muscles of the shoulder joint. Your elbows are like little wings, hence the name! J Pay attention to not jut the chin and to keep the lower ribs connected to your navel that you are still practicing good posture and form within the exercise.

As the muscles in our hands and wrists are connected to our shoulder muscles via continuous connective tissues, whenever there is tension in the muscles of the shoulder there will be corresponding tension in the entire chain. To enhance healing you can also stretch the wrists. See the attached picture. Note that the fingers that are difficult to ground represent lines of tension. Hold the stretch at least until the intensity of the stretch is diminished or to your tolerance level.

Note that the fingers that are difficult to ground represent lines of tension. Hold the stretch at least until the intensity of the stretch is diminished or to your tolerance level.

Arm balances are strong, graceful postures that build self-confidence. When teaching beginner yogis to bear weight in their hands it is imperative that their form carries the essence of good posture and that strength progressions are intelligent and gradual. Handstands and transitional pikes in vinyasas are the most advanced of the arm balances. Sadly, I have heard from students that in the modern yoga world if you cannot do fancy handstands or vinyasas you are a ‘nobody’ in yoga. Well that’s not yoga. Just as arm balances have the potential to build self-confidence their exaggeration has the potential to over-inflate the ego and identification with the body. When this leads to a shoulder injury they even have the potential to severely damage our ego! Lets practice the inward being of yoga that gives us the knowledge of true self and not the being out-there of exhibitionism that makes a circus out of the sacred art of yoga.

Always with you on the mat…

Monica

Brilliant article! Very helpful, informative and truly interesting. I LOVE the video link! Thank you!!

Thank you Beth.

Thank you for this article and the accompanying videos. I have been having this exact issue since a fall the other week. This worked wonderfully!

That’s great to hear Julie!

Thanks for letting me know.

Namaste

Monica

Thanks so much for this article!