Our necks are one of the most vulnerable parts of our body and once we have a neck problem they can be complex to resolve.

There are a few reasons why the neck cops the brunt of it. Firstly the neck or cervical spine has the greatest range of movement possible in the entire spine. This is partially due to the specific angle of the facet joints that connect each vertebra to the next but also due to the high ratio of vertebral body to disc height. This means that the vertebral discs in our neck are the thinnest and thereby the most vulnerable. Additionally, our neck is at the end of the kinematic (movement) chain of the joints of the body, whether this be via your legs, your spine or your arms. As a result, functionally our necks must accommodate for any less mobile joints and tense muscles below it and is burdened with the greatest amount of compensation for any imbalances present lower in the chain. It is for this reason that the cervical spine is the most common place for osteoarthritis (the ‘wear and tear’ type of arthritis).

One of the best ways to keep your neck happy is to give the joints more space, i.e. to lengthen it whether we are or are not moving. This can be done passively by relaxing the muscles that surround the neck or actively as in elongating the neck when we practice asana. To achieve this the shoulder blades must be drawn downward so the muscles above the shoulder blades can release. This means engaging the lower trapezius and/or latissimus dorsi muscles.

Commonly, when wanting to improve our posture we squeeze the shoulder blades together on our back. Care needs to be taken with this action. Firstly, the shoulder blades (scapulae) naturally sit at approximately a 30-degree angle on the back. A totally flat upper back is not natural and to attempt to hold this position will create tension in the neck. This action requires engagement of the rhomboid muscles. The rhomboids draw the scapulae to the spine AND draw the shoulder blades upward towards the neck. Over-activation of the rhomboids can trigger the surrounding muscles to also engage, the levator scapula (elevates the scapula) and the upper trapezius, which is often already hyperactive or over facilitated. Both of these muscles attach to your neck and head and are often involved in neck tension and pain.

When practicing bring awareness to your neck and check that you are not shortening this (or any other!) part of your spine, whether it is in a neutral position, extended in a backbend or rotated in a twist. For example, it is very common for yogis to ‘hold their neck with their hands’ when weight- bearing on their hands. The strenuous effort of balancing on our hands is often transferred to our neck. This tends to happen in even the seemingly less noxious postures like Downward Dog. Unawares we tend to tense everything from our hands to our neck. The nerves that supply the arms and hands originate from the neck and also supply the neck muscles. In Downward Dog set up your arms as a strong support creating space at the joints. Specifically check that you are not holding tension at the base of your neck.

When performing any arm balance actively lengthen your neck. In fact check that your spine lengthens uninterrupted from your sacrum to your head. The muscles that we use to grip and push the floor away (that’s what you do so you don’t kiss your mat!) do NOT connect up to our neck. You may need to extend your neck and then do so specifically and with a long neck. When you lengthen your neck you ensure space at the joints and non-recruitment of unnecessary muscles. If you stay true to a long neck it will help you to instead recruit those shoulder girdle muscles that are designed for the job, making your arm balances stronger and lighter. The other option is that you may find that you are not YET strong enough to perform the posture. The only mistake is to demand that your neck muscles compensate for a lack of shoulder girdle strength.

Inverted asana where our head does not touch the floor (eg, Prasarita Padottanasana) are a sweet opportunity to relieve the normal compressive forces on the neck and even apply some traction with your head as the heavy weight : ). As you enter each variation, when you take an extra breath with your hands on your hips, exaggeratedly press your hands down onto your hips. Feel how this action activates the muscles below your shoulder blades (lower trapezius), which automatically releases the muscles above your shoulder blades (upper trapezius). Additionally, in Prasarita Padottanasana C with your fingers interlaced behind your back, before you fold forward, take your left ear towards your left shoulder. Take a couple of breaths here and then do the other side… you may be surprised at the tension you carry in these muscles!

Sadly the neck is probably one of the most ignored parts of our bodies when we practice asana. Shortening the neck or any part of our spine when performing asana implies that we are using too much effort, which is usually ineffective and counter-productive. Practice with careful awareness of your spine and neck to avoid and release neck tension and to keep you and your cervical spine happy and mobile.

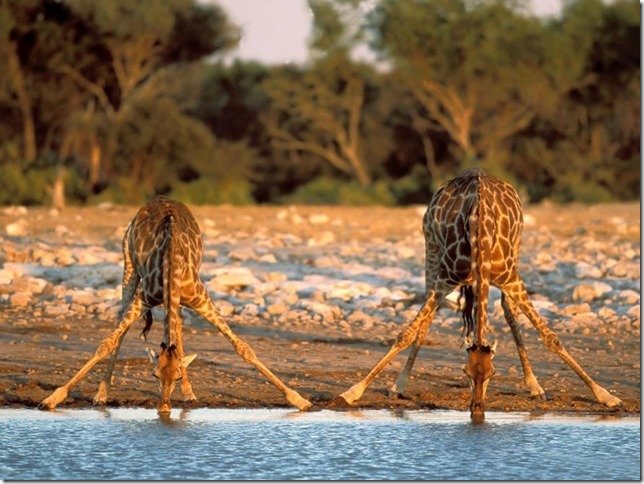

BTW did you know that all vertebrates, including giraffes have seven cervical vertebrae, just like us?!

Always with you on the mat… Monica