With yoga in they eyes of many modern practitioners reduced to posture (asana) here a timely revisit of what Patanjali, the ancient codifier of yoga, said about this third limb. This is the first part of Patanjali’s definition, given in sutra II.46.

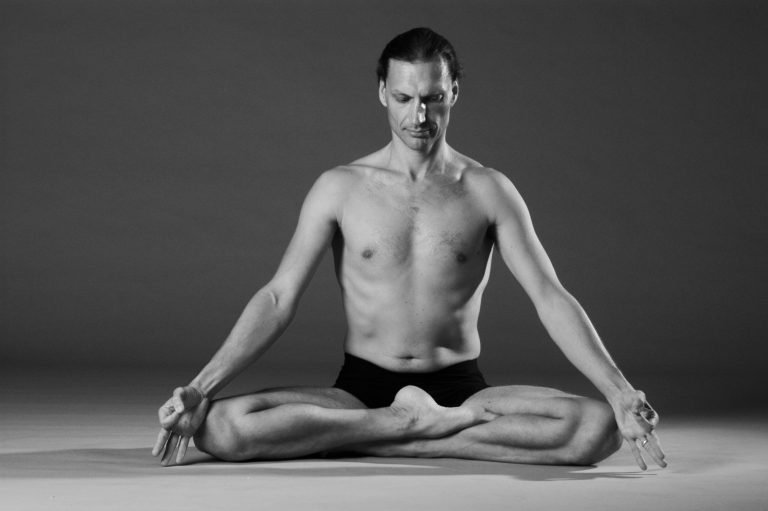

II.46 Posture must have the two qualities of firmness and ease.

With the effects of the restraints (yamas) and observances (niyamas) given, Patanjali concludes his description of the first two limbs. He has described these two limbs only briefly. His descriptions of the first five limbs are in fact very concise, hinting at the fact that the Yoga Sutra addresses the more or less established student.

He will now cover the third limb, asana, in three stanzas. That doesn’t mean posture is unimportant. Had that been the case, Patanjali would not have declared asana to be one of the eight major aspects of yoga. He will cover pranayama in only five stanzas and pratyahara in just two.

Most of the Yoga Sutra deals with samadhi and its effects. It is here that Patanjali’s main interest lies. Teachers such as Svatmarama and Gheranda devoted themselves almost exclusively to the first four or five limbs, which does not mean they regarded samadhi as an inessential form of practice.

Patanjali uses two qualities that are diametrically opposed to describe posture: firmness and ease. If the posture is to be firm, effort will be required – contraction of muscles that will arrest the body in space without wavering. Ease on the other hand implies relaxation, softness and no effort. Patanjali shows here already that posture cannot be achieved unless we simultaneously reach into these opposing directions.

These directions are firmness, which is inner strength, and the direction of ease, which brings relaxedness.

Vyasa gives a list of postures in his commentary to show that yogic posture (yogasana) according to yoga shastra (scripture) is meant here, and not just keeping one’s spine, neck and head in one line. He also says that the poses become yoga asanas only when they can be held comfortably. Before that they are only attempts at yoga asana.

Shankara elaborates further to say that, in yoga asana, mind and body become firm and no pain is experienced. The firmness is needed to block out distractions since, after asana has been perfected, we want to go on to pranayama, concentration and so on.

Mention of the absence of pain is interesting. If the field of perception is filled with pain, the mind will be distracted. Patanjali’s definition of posture as ease automatically eliminates that which causes pain. If you are in a pose and experience pain you will not be at ease. The widespread tendency in modern yoga to practise the poses in such a way that they hurt leads to being preoccupied with the body. This is by definition not yoga asana.

According to scripture, in asana the limbs have to be placed in a pleasant and steady positioning so as not to interfere with the yogi’s concentration. The inner breath (prana) is then arrested and moved into the central channel (sushumna). Sushumna will eat time, and the fluctuations (vrtti) of the mind will be arrested. Meditation on Brahman will then arise.

Asana is thus a preparation for samadhi, whereas practices that lead to pain will increase the bond between the phenomenal self (jiva) and the body, which in itself is the yogic definition of suffering. Those practices might be gymnastics, they possibly could even be healthy, but they are not yoga, which is recognising the false union (samyoga) of the seer (drashtar) and the seen (drshyam).[1]

[1] Sutra II.17

This is an excerpt of my 2006 commentary on Patanjali’s sutra and associated subcommentaries. It is contained in Ashtanga Yoga Practice and Philosophy.